Rank-Select optimizations in BitMagic Library

Anatoliy Kuznetsov. Oct, 2018. anatoliy_kuznetsov@yahoo.com

Introduction

Population counting (or bit counting) is a common operation used in databases, information retrieval systems, as a building block for address space flattening, ISAM, etc. One very important use case for bit-vectors is Rank and Select operations, which are the cornerstone for succinct (memory compact) data structures.

Rank operation

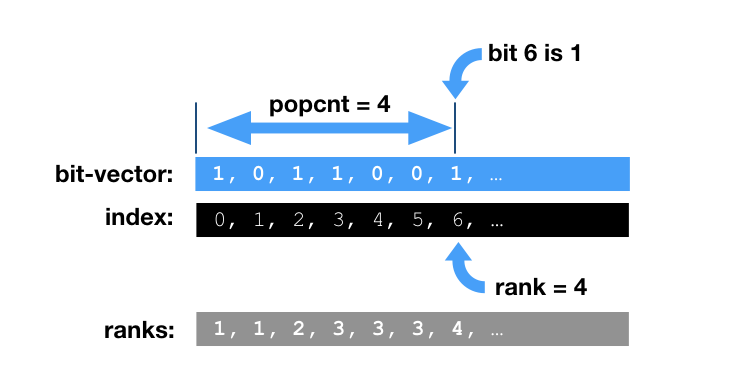

Lets define a bit-vector [0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1] (position 0 on the left). The operation rank(i) is defined as the number of set bits (1s) in the range [0, i]. Another aspect of rank operation is whether bit i is set or not. In the example above, bit-vector element 2 of [0, 0, 1, ...] would have rank=1. Element 4 would have rank 2 [0, 0, 1, 0, 1, ...]. Please note, if the whole bit-vector is saturated with 1s - rank of elements would be equal to position (plus 1). If we know position and rank we can quickly tell, how many 0 elements we have. This property is very important for constructing succint data structures.

Succinct data structures

In computer science, a succinct data structure is a data structure which uses an amount of space that is "close" to the information-theoretic lower bound, but (unlike other compressed representations) still allows for efficient query operations. Why rank is a cornerstone and how to use bit-vectors for succinct data structures? Lets take an array (of characters) as an example. If the array happens to have high content of 0 elements there is always a temptation to get rid of them, not to store not to search.

(0, 0, A, 0, B, C) - character array

[0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1] - index bit-vector

What we did here is we added an extra bit-vector matching one to one to our original array. Doing this does not save memory, right? Correct, but stay with me here. The idea of succinct structures is to transform the original array. Extra bit-vector can answer the question if the original element is zero (or any known value for that matter) and it can answer it in quick constant time. This is good, but show me my savings!

(A, B, C) - character array freeze-dried (no 0 elements)

[0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1] - index bit-vector

What we now did is we dropped the zero elements, kept an extra bit-vector. We can still tell if the original element is 0 or not (bit-vector lookup). And we can tell the RANK. Please note that rank of elements (minus 1) - gives us the index of the same element in the original array.

Lets pause and quickly verify, rank of element 2 is 1, 1-1=0, so element 2 has new index 0 and it is 'A'. Element 3 is 0 (we dont need RANK to tell that). Element 4 - rank 2, index = 1, value = 'B'.

The savings model of succinct data structures is often based on keeping an extra bit-list and dropping the actual elements which are known (to be 0 or something else). In our example we drop 8-bit characters, but it could be ints, structures, strings, etc. Succinct data structures can be quite sophisticated, operate on bit-levels, but now we get the nutshell idea. For very dense structures succinct operation may not make sense.

Please note, that described technique is NOT a compression in its classic sense. We transformed the data, we can still access elements without decoding the whole thing (or a page). Succinct transformation can be used together with compression algorithms, but it is not a compression.

Isn't it slow? Yes and no. Obviously, succinct operation requires extra memory access and an extra computation. The factor to consider here is that computation (raw CPU power) is cheap and memory is slow and expensive. This allows us a trade of CPU cycles for bandwidth. Modern CPUs equipped with HW bit-aceleration instructions, SIMD vector units can actually make this trade very profitable.

Search in succinct array

Lets take a look at our distilled data again from the search perspective.

(A, B, C) - character array freeze-dried

[0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1] - index bit-vector

We obviously can tell zero elements. We obviously can do linear search in the distilled value vector. We can do a binary search if our vector is sorted (incidentally it is actually sorted). Our succinct transformation was order preserving. The missing thing is that we cannot tell the original index. Can RANK be reversed? Yes it can! Operation reverse to rank is called SELECT.

SELECT operation and its use in search

Select operation is a seach of a rank. Lets go back again to our vector.

(0, 0, A, 0, B, C) - original array

(A, B, C)

[0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1]

Say we searched for 'C', and identified its succinct index as 2 (rank 3). Lets SELECT the original index. Rank 3 means, we need to rewind the index bit-vector, count all 1s from the start until we find third set bit. This is good, we can do it, third set bit has index 5, which is 'C' in the original array. We reversed the search.

We just modeled a succinct data structure, with access to the original data and search, returning us the reference (index) of the original data.

The interesting implication is that in many cases, search in succinct data structure would be faster than seach in the original structure. This is a somewhat controversial statement but I am ready to defend it. There are many factors here, but there is one single, the most important aspect: RAM access costs. When we look at high level CPU utilization and see it is 100%, it is very, very often means, that our CPU is busy, but it is busy loading data from memory (and processing it). That processing part way too often experience hidden starvation (waiting for memory) and while processor looks busy, it is actually idle in terms of actual computations. Any measures, which allow us to reduce RAM to CPU traffic increases CPU efficiency and allow us to use otherwise hidden CPU potential. In our case, not loading and not processing suffcient number of zero or otherwise commonly known elements often means faster search, despite an extra step of SELECT operation on index bit-vector.

Real life data structures involved in big-data knoweledge graphs are very often sparse, sometimes randomly sparse. Succinct algorithms allow us to fit such data in memory an operate on it from memory.

Perfomance optimization challenges and opportunities

Now we understand how important it is to have Rank-Select operations for good succinct data structures. In serious production systems the size of the bit-vector can be huge. Search systems, genome analysis applications - all can produce large vectors where direct rank and select operations will be prohibitevely slow if naive implementation would be doing direct end-to-end bitwise scanning.

What options do we have for optimization?

Optimization of Rank-Select operations boils down to two big categories: algorithmic macro optimization and close to hardware micro-optimization. Macro optimization relies on secondary structures (rank-select index) to quickly find the target area in our index bit-vector. The challenge here is to keep such structure reasonably compact (otherwise it defeats the purpose) and avoid masive POPCNT based bit-vector scanning.

Rank-Select index is often implemented using skip list of blocks. When we know population count of a block we can skip it. This approach is ok, but not good enough for performance critical hotspot like rank-select. Skipping is a linear operation and we target rank-select as close to constant speed or log(n) as possible.

Rank select index that BitMagic implements now can be described as a two layer block-subblock index.

A little bit on BitMagic internals. bm::bvector<> - compressed bit-vector class

implements block based memory management, where each block holds 65536 bits (size of unsigned short).

This block size is used for the top-level rs-index array. Top level block array keeps population count from

bit 0 to the end of the block. In other words this is a running count of population counts of all blocks up to N.

Quick example. Block 0 has population count of 10 (index value 10), bit block 1 - population count 100, index value 110 (10+100). Index block N would be BitCount(N) + RsIndex(N-1). This makes a growing unsigned integer sequence (with duplicates). Block level rs-index keeps top level rank. As such the access to the top level rank has a constant speed. Bit-count of a particular block is index[N] - index[N-1].

SELECT operation for top level index uses binary search O(nlog(n)) to locate target block. More about optimization of this binary search later.

Top level block index allows us to quickly narrow down our RANK-SELECT within one block of 65536 bits. This is where we keep the second layer of the index. Bit block index splits block into 3 sub-blocks, and keeps population count for sub-blocks 0 and 1. Bit count for sub-block 3 can be calculated using top level index.

[ 10 ], [ 110 ], .... [ N ]

[ ], [ ], [20, 65, X ]

Quick example above shows, that block X (bit count N) has two sub-blocks with population count 25 and 65. Third virtual sub-block has bit-count X as bitcount(N) - (20 + 65). Since block bit-count is 65536 (unsigned short), we only keep 2 short (16-bit) unsigned ints per block as a second level structure. So far we have 32-bit int per block plus 2 16-bit ints for sub-block. Sub-block indexing allows us to narrow down our search to a sub-block (65535/3) level.

This is where BitMagic library dives into the bit-block to do computation there. The big picture is that BitMagic implements hybrid scheme, using RS index to narrow down our rank-select and hardware accelerated search within the bit-block.

Rank operation within sub-block

Lets review the algorithm how we implement rank algorithm within sub-block.

sub-block 0 sub-block 1 sub-block 2

[ 00001010111100010100 | 000000001010100110 | 00000010100010011 ]

^

|

+ ------------------------ Rank position R0

Lets review an example, where we need to compute rank for position R0 where R0 is within sub-block 0 boundaries.

One way to do it is to compute bit-count in the interval [0...R0], another is to compute interval [R0+1 ...] (R0 to the sub-block end) and use subtraction BITCOUNT(Sub-block 0) - BitCount([R0+1 ...]) for the final result.

sub-block 0 sub-block 1 sub-block 2

[ 00001010111100010100 | 000000001010100110 | 00000010100010011 ]

<---------> ^

[0..R0] |

+ ------------------------ Rank position R0

sub-block 0 sub-block 1 sub-block 2

[ 00001010111100010100 | 000000001010100110 | 00000010100010011 ]

^

| [R0+1..]

+ ------------------------ Rank position R0

Logically choosing the shortest bit-substring to a known boundary minimizes the bit-count expense. The worst case scenario here is that our position is somewhere in the middle and we have to compute the bit-count on the bit-string of 1/5th of our block size (approximately 11K-bit). This is about 170 64-bit words (1360 bytes), 21 cache line fetches.

Contemporary CPUs offer HW acelerated POPCNT, with AVX2 and AVX-512 it is possible to bit HW POPCNT using parallel algorithms, so it is not that bad as a trade-off between index memory consumption versus speed.

Overall analysis shows that hybrid, rs-indexed RANK operation is "near constant speed". Worst case performance is capped by HW POPCNT implentation, plus memory access for approximately 21 64-byte memory lanes plus two memory fetches from rs index block and sub-block level indexes.

Some sources suggest RS-index should be implemented as interleaved structure so super-block and sub-block fetch is just one call (1 32-bit word and 2 16-bit fits into one 64-bit word). This approach is reasonable and is the best for RANK, but creates some complications for SELECT so BitMagic library chooses a non-interleaved approach.

Optimizations of SELECT operation

SELECT as a part of the search algorithm is very important and more difficult to optimize. While RANK is near constant speed, SELECT at its first step needs O(nlog(n)) lower bound binary search in unsigned integer array. Properties of the binary search are very well known. Lets just discuss one particular aspect which is important for our optimization: lower bound search over small arrays of scalar native types (like ints) is slower than linear scan because of memory access pattern and superscalar (parallel) nature of modern CPUs and their capability to do speculative execution of instructions.

So we choose to use hybrid search technique, which first narrows down to a small window with binary search, then sprints into linear scan.

inline

unsigned lower_bound_linear(const unsigned* arr, unsigned target,

unsigned from, unsigned to)

{

for (; from <= to; ++from)

{

if (arr[from] >= target)

break;

}

return from;

}

inline

unsigned lower_bound(const unsigned* arr, unsigned target,

unsigned from, unsigned to)

{

const unsigned linear_cutoff = 32;

unsigned l = from; unsigned r = to;

unsigned dist = r - l;

if (dist < linear_cutoff)

{

return bm::lower_bound_linear(arr, target, l, r);

}

while (l <= r)

{

unsigned mid = (r-l)/2+l;

if (arr[mid] < target)

l = mid+1;

else

r = mid-1;

dist = r - l;

if (dist < linear_cutoff)

{

return bm::lower_bound_linear(arr, target, l, r);

}

}

return l;

}

AVX2 accellerated index search

The final linear scan can also use SIMD optimizations. Lets review the AVX2 version here.

unsigned avx2_lower_bound_scan_u32(const unsigned* arr,

unsigned target,

unsigned from,

unsigned to)

{

const unsigned* arr_base = &arr[from]; // unrolled search base

unsigned unroll_factor = 8;

unsigned len = to - from + 1;

unsigned len_unr = len - (len % unroll_factor);

__m256i mask0x8 = _mm256_set1_epi32(0x80000000);

__m256i vect_target = _mm256_set1_epi32(target);

__m256i norm_target = _mm256_sub_epi32(vect_target, mask0x8); // (signed) target - 0x80000000

int mask;

__m256i vect80, norm_vect80, cmp_mask_ge;

unsigned k = 0;

for (; k < len_unr; k += unroll_factor)

{

vect80 = _mm256_loadu_si256((__m256i*)(&arr_base[k])); // 8 u32s

norm_vect80 = _mm256_sub_epi32(vect80, mask0x8); // (signed) vect4 - 0x80000000

cmp_mask_ge = _mm256_or_si256( // GT | EQ

_mm256_cmpgt_epi32(norm_vect80, norm_target),

_mm256_cmpeq_epi32(vect80, vect_target)

);

mask = _mm256_movemask_epi8(cmp_mask_ge);

if (mask)

{

int bsf = bm::bsf_asm32(mask); //_bit_scan_forward(mask);

return from + k + (bsf / 4);

}

} // for

for (; k < len; ++k)

{

if (arr_base[k] >= target)

return from + k;

}

return to + 1;

}

AVX2 version combines loop unrolling, AVX2 based vector comparison and uses BSF (bit scan forward) instruction for first set bit search. It compares 8 integer elements at a time with one if (almost branchless). One complication here is that Intel SIMD set operates on signed integers and our structure of RS-index uses dense unsigned array to keep running counts...

The not so obvious hacks for this case are well described at https://fgiesen.wordpress.com/2016/04/03/sse-mind-the-gap/. Long story short it uses arithmetic properties equations a > b (unsigned, 32-bit) is the same as (a - 0x80000000) > (b - 0x80000000) (signed, 32-bit) to exclude sign bit and still be true on comparison. Tricks like this make possible parallel SSE/AVX comparisons on SIMD vectors.

Another trick is to use HW instructions BSF (or LZCNT) to identify the first found value without sequential

analysis of comparison results provided by SIMD _mm256_movemask_epi8().

Use of small tricks like that improve speed of good old plain vanilla binary search. For critical operations these optimizations are totally worth the trouble, since it is going to be called million times and even small gain pays off.

Going back to possible interleaved memory layout for block and sub-block levels of RS index. Clearly, interleaved layout would have negative impact on linear scan, because it would reduce the efficiency of SIMD comparison, effectively making it 4 integers at a time, instead of 8, plus extra complexity to ignore false sub-index hits.

BMI1/BMI2 optimizations

Intel and AMD processors offer two extra esoteric sets of instructions, called BMI1 and BMI2. Bit-manipulation instructions. BMI2 instructions are quite useful for our SELECT purposes.

Quick recap here. Accelerated SELECT is implemented as a multi-stage operation. First it is doing hybrid binary search, then it narrows down within a sub-block, then goes into bit-string, where it uses HW POPCNT to find the right word and THEN it needs to do SELECT within one integer word.

That last stage of select requires bit fiddling and it uses iterative approach (naive implementation).

unsigned word_select64_linear(bm::id64_t w, unsigned rank)

{

BM_ASSERT(w);

BM_ASSERT(rank);

for (unsigned count = 0; w; w >>=1ull, ++count)

{

rank -= unsigned(w & 1ull);

if (!rank)

return count;

}

BM_ASSERT(0); // shoud not be here if rank is achievable

return ~0u;

}

In the presence of HW POPCNT we can produce faster, iterative variant of SELECT scan.

unsigned word_select64_bitscan(bm::id64_t w, unsigned rank)

{

BM_ASSERT(w);

BM_ASSERT(rank);

BM_ASSERT(rank <= bm::word_bitcount64(w));

do

{

--rank;

if (!rank)

break;

w &= w - 1;

} while (1);

bm::id64_t t = w & -w;

unsigned count = bm::word_bitcount64(t - 1);

return count;

}

Alernative implementation may choose BMI1, which would BLSR, BLSI, and TZCNT instructions.

unsigned bmi1_select64_tz(bm::id64_t w, unsigned rank)

{

BM_ASSERT(w);

BM_ASSERT(rank);

BM_ASSERT(rank <= _mm_popcnt_u64(w));

do

{

if ((--rank) == 0)

break;

w = _blsr_u64(w); // w &= w - 1;

} while (1);

bm::id64_t t = _blsi_u64(w); //w & -w;

unsigned count = unsigned(_tzcnt_u64(t));

return count;

}

Please note, that BLSR, BLSI are BMI1 instructions for w &= w-1; and w & -w.

Despite hopes BLSR/BLSI tricks does not produce faster code...

Possible anectdotal explanation is that all instructions use

the same HW block and limit out of order superscalar execution, which is apparently at play for less specialized version.

Another BMI1 contender uses POPCNT and LZCNT, trying to narrow it down faster and turn OFF extra bits. Same result, no decisive advantage here.

unsigned bmi1_select64_lz(bm::id64_t w, unsigned rank)

{

BM_ASSERT(w);

BM_ASSERT(rank);

BM_ASSERT(rank <= _mm_popcnt_u64(w));

unsigned bc, lz;

unsigned val_lo32 = w & 0xFFFFFFFFull;

unsigned bc_lo32 = unsigned(_mm_popcnt_u64(val_lo32));

if (rank <= bc_lo32)

{

unsigned val_lo16 = w & 0xFFFFull;

unsigned bc_lo16 = unsigned(_mm_popcnt_u64(val_lo16));

w = (rank <= bc_lo16) ? val_lo16 : val_lo32;

}

bc = unsigned(_mm_popcnt_u64(w));

unsigned diff = bc - rank;

for (; diff; --diff)

{

lz = unsigned(_lzcnt_u64(w));

w &= ~(1ull << (63 - lz));

}

lz = unsigned(_lzcnt_u64(w));

lz = 63 - lz;

return lz;

}

The BMI2 instruction set coming with AVX2 offers high performance solution to SELECT problem. It is based on PDEP and TZCNT instructions and can be hard to decipher.

unsigned bmi2_select64_pdep(bm::id64_t val, unsigned rank)

{

bm::id64_t i = 1ull << (rank-1);

bm::id64_t d = _pdep_u64(i, val);

i = _tzcnt_u64(d);

return unsigned(i);

}

Good explanation of PDEP/TZCNT technique can be found here: https://haskell-works.github.io/posts/2018-08-22-pdep-and-pext-bit-manipulation-functions.html In presence of AVX2 this implementation is observed to be 3x faster than any other variant. There is a concern about slow AMD implementation of BMI2 PDEP(probably uses micro-code). It needs to be tested, I hope that the final impact of somewhat slower implementation may not be that big. Need more tests with AMD.

Rank-Select example

Quick sample on how to construct and use the RS index in your program.

#include "bm.h"

int main(void)

{

try

{

bm::bvector<> bv { 1, 20, 30, 31 }; // init a test bit-vector

// construct rank-select index

std::unique_ptr<bm::bvector<>::rs_index_type>

rs_idx(new bm::bvector<>::rs_index_type());

bv.build_rs_index(rs_idx.get());

// lets find a few ranks here

//

auto r1 = bv.rank(20, *rs_idx);

std::cout << r1 << std::endl; // 2

r1 = bv.rank(21, *rs_idx);

std::cout << r1 << std::endl; // still 2

r1 = bv.rank(30, *rs_idx);

std::cout << r1 << std::endl; // 3

// now perform a search for a position for a rank

//

bm::id_t pos;

bool found = bv.select(2, pos, *rs_idx);

if (found)

std::cout << pos << std::endl; // 20

else

std::cout << "Rank not found." << std::endl;

found = bv.select(2, pos, *rs_idx);

if (found)

std::cout << pos << std::endl; // 30

else

std::cout << "Rank not found." << std::endl;

found = bv.select(5, pos, *rs_idx);

if (found)

std::cout << pos << std::endl;

else

std::cout << "Rank not found." << std::endl; // this!

}

catch(std::exception& ex)

{

std::cerr << ex.what() << std::endl;

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

References

- Alex Bowe. “RRR – A Succinct Rank/Select Index for Bit Vectors”. http://alexbowe.com/rrr/

- GPU Gems 3. “Chapter 39. Parallel Prefix Sum (Scan) with CUDA”. https://developer.nvidia.com/gpugems/GPUGems3/gpugems3_ch39.html

- A Fast x86 Implementation of Select. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1706.00990.pdf

- Bit-manipulation operations for high-performance succinct data-structures and CSV parsing. https://haskell-works.github.io/posts/2018-08-22-pdep-and-pext-bit-manipulation-functions.html

- sample17.cpp (rank-select operatoins)